Scam accounts that impersonate brokers are proliferating, luring in prospective renters with impossibly good deals and the names and faces of the city’s top rental brokers.

Photo-Illustration: Curbed

The calls started last November. They often came late at night, when Melinda Sicari, an associate broker at Douglas Elliman, was about to go to bed or already asleep, and the callers were persistent. They’d either just sent money for an apartment to a Zelle or Venmo account or were about to send it. But something made them call the broker they thought they’d been communicating with. “They would say something like, ‘I just applied for your apartment and sent you the deposit.’ Or ‘I know this is going to sound really weird, but …’”

At first, Sicari, the top rental broker at Douglas Elliman, who leads a team of six other agents, assumed the callers were clients. “Oh, which apartment?” she’d ask. But the addresses they gave her didn’t exist, nor did the prices: $950 for a Soho studio, $2,500 for a loftlike two-bed, two-bath in Greenwich Village, a Gramercy one-bedroom in a luxury doorman building for $1,800 a month. It became clear that someone was posting ads all over TikTok and Instagram with her listing images and pretending to be her when someone inquired about them. Soon, she was getting four, five, sometimes ten calls a day. “It’s a scam,” she’d tell callers as soon as she could get a word in. Some of them would be embarrassed but relieved: “I knew it was too good to be true.” But those who had already sent money, sometimes much more than the $145 “application fee,” got upset. One man called her ten times in a row from different numbers, demanding she refund his money. Occasionally, people would show up at her midtown office. “One woman who was getting an apartment for her daughter flew in from Delaware,” Sicari told me. “She came to the office on a Saturday to pick up the keys.”

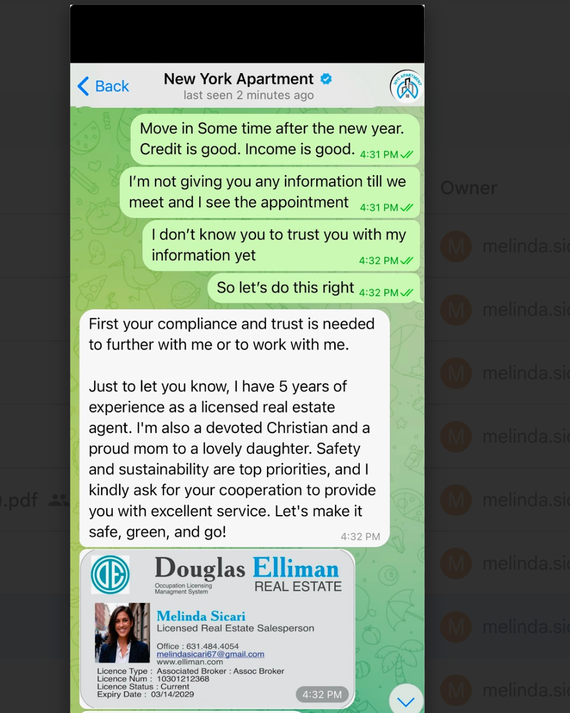

When prospective renters become skeptical, scammers often send a fake but realistic-looking business card with much of Sicari’s real information.

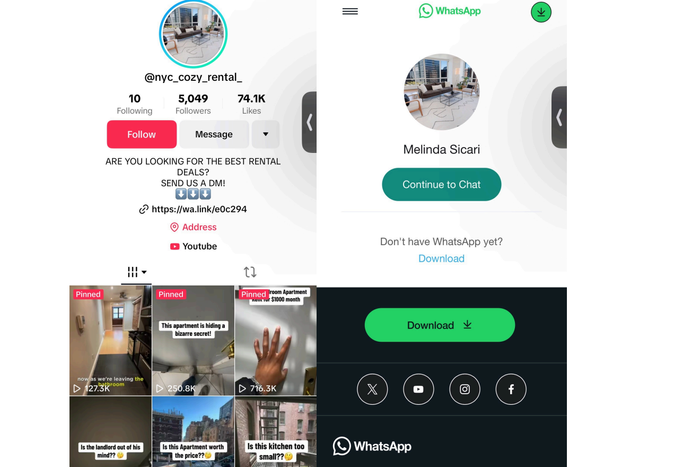

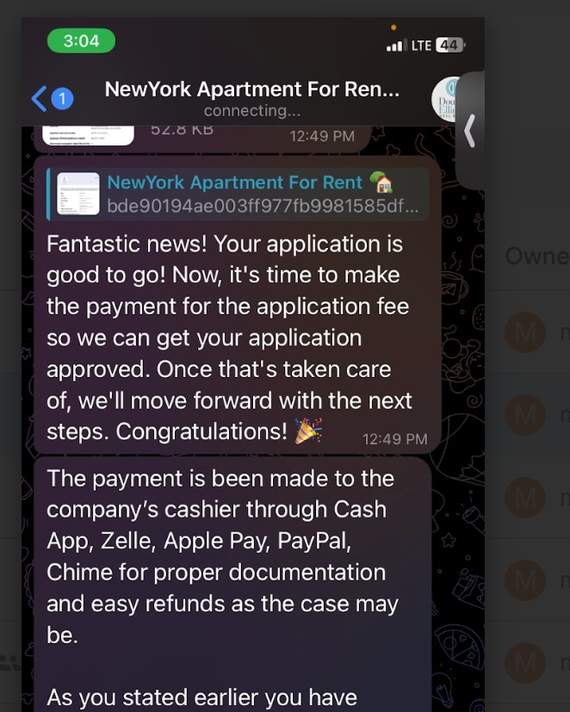

Most of the scammers impersonating Sicari are savvy enough not to use her name or photo to set up their accounts on TikTok and Instagram, where she could more easily flag them and get them removed. Instead, the profiles have nondescript names like nyc_cozy_rental, unique_listings, and regulatedapartments, and they instruct prospective renters to contact them via WhatsApp or Telegram. That’s where they start posing as the broker. “My name is Melinda Sicari, a licensed real estate professional. Thank you for your concerns,” one wrote in a WhatsApp response to someone inquiring why they wouldn’t send her a link to the apartment listing. “My track record includes numerous successful deals and satisfied clients.” They sent a link to Sicari’s actual StreetEasy page. Often, they also include an image of a business card with all of Sicari’s real info — only the real-estate license number is fake. That’s often enough to satisfy the apartment hunters doing a quick Google search to confirm that Sicari is a real broker. I asked her how many people she’s been contacted by who’ve actually sent the scammers money. “Hundreds,” she told me.

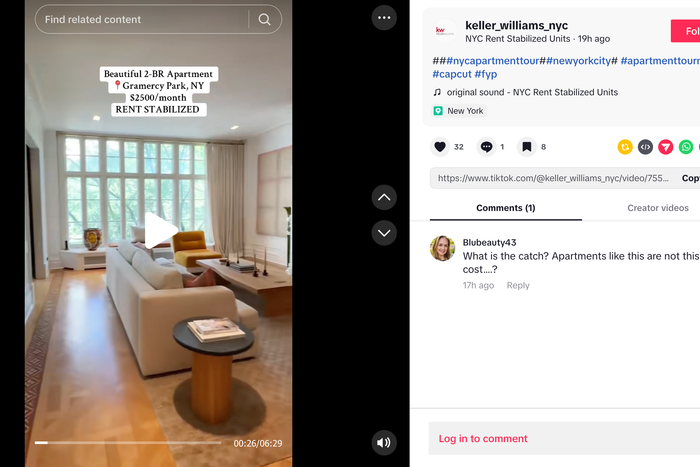

Most of the people losing money are out-of-towners, according to Sicari — often parents trying to lock down an apartment for their early-20-something kids who’ve been told they need to send in money now, or they’ll lose this great place. They may assume their kid has talked to someone on the phone instead of just on WhatsApp. Others may take the video tour as proof that an apartment is real, even though such tours are all over the internet, and it’s easy enough to lift a reel of a $15,000-a-month rental and slap on a new voice-over and a $2,200 price. Many out-of-towners are also, understandably, a bit out of touch with the New York City market — not knowing that the scam prices aren’t just good, but unreal, or that brokers don’t post reams of rent-regulated apartments to TikTok — you’re lucky if you stumble across one on StreetEasy, and they’re rarely in prime Manhattan neighborhoods where landlords have had every incentive to try and destabilize them over the years.

A screenshot of one of the scam accounts and an account posing as Sicari.

But New Yorkers get scammed, too. After all, to land a great apartment, you have to be willing to put up with a certain amount of sketchiness: application fees that exceed the cost of a credit check (capped at $20 by law), handing over a “good faith” deposit to hold a place while your application is processed (illegal), paying a broker’s fee above 15 percent (quasi-legal), and offering more than the asking price (legal but completely demoralizing). It doesn’t help that the current rental market, which has continued to set records month after month, is fertile ground for these types of cons. When you’ve spent weeks or months sifting through uninspiring, overpriced listings and a gem suddenly pops up, it can be hard not to reach out just to see. Several victims who’ve contacted Sicari are rental-voucher recipients, who often struggle to find apartments or brokers to work with them at all. (One TikTok scam account I came across claimed it was “Section 8 approved.”) And it’s not like renters have a lot of time to mull things over: You know you’re competing with parents with bigger bank accounts or tech bros making half a million a year who can offer above ask, so you scramble to send over your most sensitive information, from Social Security numbers to bank statements, to someone you’ve just met.

So it didn’t strike LaLa Holston-Zannell, a senior campaign strategist at the ACLU, as all that strange when a broker she’d met on TikTok — Sicari, or so she thought — sent over a rental application with a Douglas Elliman letterhead and asked for a $145 application fee. Nor did the apartment, a one-bedroom in an amenitized Midtown East doorman building going for $2,500, seem like pure fantasy — Holston-Zannell was paying $2,000 a month for a studio in a no-frills building nearby — it was more like the kind of thing you’d have to move fast on.

After chatting on WhatsApp and being told she could see the apartment the next day, Holston-Zannell sent $145 via Apple Pay. And then she heard nothing. She pressed, they dodged: They hadn’t received her payment. She sent proof, and after more silence, she got suspicious and contacted Sicari, who told her she’d been swindled. “I don’t trust anyone anymore,” says Holston-Zannell, who managed to get the money back from her bank in the end. She still hasn’t found a one-bedroom.

A scammer impersonating Sicari tries to close the deal and get the renter to send in an “application fee.”

One graphic designer I spoke with fell for what seemed to be a dream apartment in her old neighborhood. She wanted to move back to Fort Greene, where she’d rented a $2,500-a-month studio before relocating to L.A. in 2020. But five years later, most of the one-bedrooms were going for upwards of $4,000. Then she saw a lovely parlor-floor one-bedroom on Craigslist for $2,500 a month. Some things were a little weird — it was clearly a brownstone, but the listing said there was a gym in the building. Still, she didn’t think too much about it. The person she wrote to said he was the tenant and that he and his wife, who was undergoing cancer treatment, were relocating temporarily, so they didn’t really care about making money on the rental. But he also said that the more she paid up front, the less the overall rental price would be. “I should have realized it was unrealistic, but I was just so excited,” the woman told me. She couldn’t actually see the apartment — allegedly because of the wife’s treatments — but the man sent a link to a legit-looking video. She was about to send a wire transfer of $2,000 when a friend snapped her out of it. “She was like, ‘I would never pay before seeing the unit!’” When she Googled the wire-transfer address, it was a Walmart in South Carolina. She did more research and realized that the unit, in a DeKalb Avenue townhouse, had rented the previous June for $5,200 a month.

When she called the listing agent, Dan Chen at Corcoran, he told her the scammer had been stealing those particular listing photos for over a year. Every time he sees them pop up, he flags the listing, but it’s like playing whack-a-mole. Chen told me that even at $5,200, it’s a hot apartment — “Each time I’ve listed it, it ends in a bidding war, even with a 15 percent broker’s fee.” A floor-through one-bedroom with soaring ceilings, original fireplace mantels, ornate moldings, and parquet floors, “it checks all the boxes of why people want to live in a brownstone,” he says. Which is probably why it’s been so enduringly popular with scammers: They know what people want.

Sicari pointed out that in this rental market, everything remotely good moves fast. “Rentals go so quickly,” she says. If an amazing deal has been up online for days and a broker gets back to you right away and tells you it’s still available, “it’s not real.”

Real-estate scams have been taking in gullible New Yorkers for decades, probably centuries, now. But never have the tools at scammers’ disposal been so convincing, nor has reaching so many potential victims been easier. With so many brokers using TikTok and Instagram to promote their listings, it’s possible to conduct the entire transaction online. And the medium can be pretty persuasive. “People fall prey because the visuals are so slick on TikTok — the edits are really good and the apartments look beautiful,” says an apartment hunter who almost fell for a Sicari impersonator. When I contacted the NYPD and New York attorney general’s office to see if there had been an uptick in real-estate scams in the last five years, neither had data to share with me. But according to the FBI, 624 people in New York State lost a total of $12.1 million in real-estate scams last year, more than double the $5.7 million lost the year before. Brokers say the impersonators seem to be proliferating in the social-media age.

When I met with Sicari in her office building, I had to wait at the security desk downstairs for her to come get me — a new protocol put in place after duped renters started showing up at the office. Upstairs, she explained what a nightmare the last nine months have been as she pulled up months of files documenting the scams and her attempts to stop them. The scammers typically post a few times a week, and for several days afterwards, she’s slammed with calls, emails, and DMs from their victims. Dealing with the aftermath has become like a second job, on top of the 30 to 40 rental deals her team does a month: She has to talk down the angry would-be renters, provide information to police precincts so victims can file reports, contact social-media and online-banking apps to report fraud and impersonation, and post her own videos on social media warning renters about the scammers. Douglas Elliman’s lawyers have tried to intervene on Sicari’s behalf, but they’re hardly more effective than she is at getting social-media and financial platforms to pull down videos and accounts. And often, the apps offer little recourse. “I get messages like, ‘Your request has been denied,’” she says. “Or, ‘Well you can’t really prove it.’ What do you mean? I’m Melinda Sicari. There’s someone out there using my name and profile and there’s nothing wrong with it?”

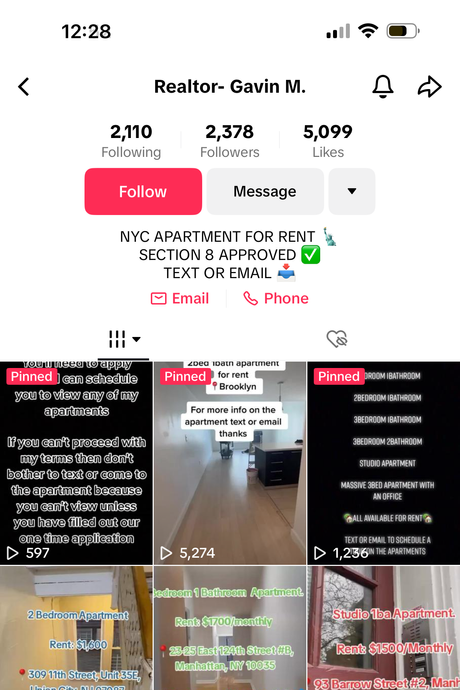

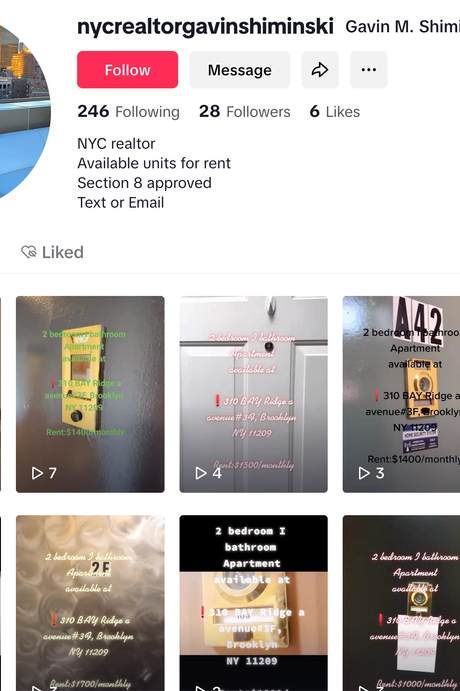

Gavin Shiminski, another Douglas Elliman agent, told me that the scammers who impersonated him on Instagram had amassed such a sizable following that when he reported them, Instagram ruled that he was the imposter. And because so much customer service is automated, it took him forever to reach an actual human to sort it out. He added that he was worried about the professional repercussions of the fraud — what if victims make real complaints about the fake him? “I got an email through my work account — this woman had paid $250. She was really upset. I was like, ‘Do I reimburse you?’” Eventually, Instagram introduced paid verification, which squelched the Instagram impostors, and he decided to stop using TikTok. “The scammers kept on changing their user names. It got too difficult. I didn’t want to provide them with any more content,” he said. “The last recording I did was a video saying, ‘This is not me.’” When I asked TikTok about several scam accounts that had been impersonating Sicari, a representative told me they’d removed them after receiving my email and that “TikTok takes a number of steps to better protect our community, including removing scam content from the platform when we find it.” Instagram did not respond to a request for comment.

Two accounts impersonating Shiminski, who now pays for verification on Instagram and has abandoned TikTok

Two accounts impersonating Shiminski, who now pays for verification on Instagram and has abandoned TikTok

But it isn’t just the scammers who are impossible to pin down. It’s that their offense — stealing brokers’ identities to steal other people’s money — seems to exist in a gray area of the criminal justice system. Sicari says that when she’s contacted the police, they tell her the victims who’ve lost money need to report the theft to their local precincts. But as for Sicari, a victim of identity theft minus the financial theft, they can’t help her. (The NYPD wouldn’t comment specifically on Sicari’s case.) Sicari has traced Venmo and Zelle transactions to other U.S. states, but it’s just as likely that the scammers are based abroad, as some of the messages sound AI-generated and are otherwise awkwardly phrased: “First your compliance and trust is needed to further with me or to work with me,” was one response to a renter who balked at filling out an application. Other messages sent by her impersonators included, “I’m also a devoted Christian and a proud mom to a lovely daughter” and “Let’s make it safe, green, and go!” (The weird syntax might be the one saving grace of the scam, as it tips some people off that the person they’re talking to might not actually be a Manhattan broker.) Sicari also wonders whether the fact that the individual amounts are often relatively small and spread out among multiple precincts (and other cities and states) means that it’s being registered by law enforcement as petty theft, and therefore less of a priority, even though the overall amounts being stolen may add up to tens or even hundreds of thousands of dollars.

If it wasn’t a local police issue and more of a cybercrime without geographic limits, then was it a statewide or even federal issue? I also reached out to the FBI, the Manhattan DA, the Federal Trade Commission, the New York attorney general’s office, and several legal and academic experts. Everyone I spoke with agreed that what I described sounded bad but couldn’t tell me exactly what this was besides, of course, a scam — fraud? Identity theft? Impersonation? — or how to stop it. They just offered boilerplate advice on how to avoid scams. Sicari showed me two complaints she filed with the FBI earlier this year, but no one from the agency ever reached out to follow up. Stealing real people’s professional identities to steal other people’s money does, however, seem to be a burgeoning industry. One person who nearly fell for a Sicari impersonator told me that he’d also been contacted by scammers impersonating real hiring managers at companies — presumably hunting for data, not money. And the New York Times recently reported that scammers are creating deep fakes of prominent doctors to sell quack cures like “liquid pearls” and build up their YouTube followings offering bogus health advice.

Finally, I decided it was time to talk to a scammer myself. I was a little wary, considering what had happened to Sicari when she reached out to them directly on Telegram. She told the scammers that she’d reported “several instances of you trying to collect funds with my name” to the NYPD, adding, “I kindly ask you to stop.”

“Hello I will stop on only one condition,” they replied. “Are you willing to go with my condition?” That’s when she blocked the account.

Sicari believes that contacting the scammers directly might have led to what happened over Memorial Day weekend: Someone hacked into her StreetEasy account and lowered all the prices on her listings to rents in the $1,000s and $2,000s. She was barraged with hundreds of emails, messages, and calls from interested renters as she struggled to get ahold of someone at the listing site to help her get back into her account over the holiday weekend.

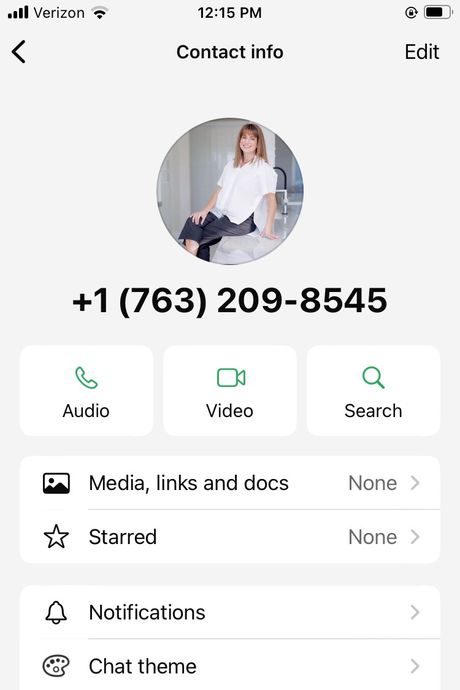

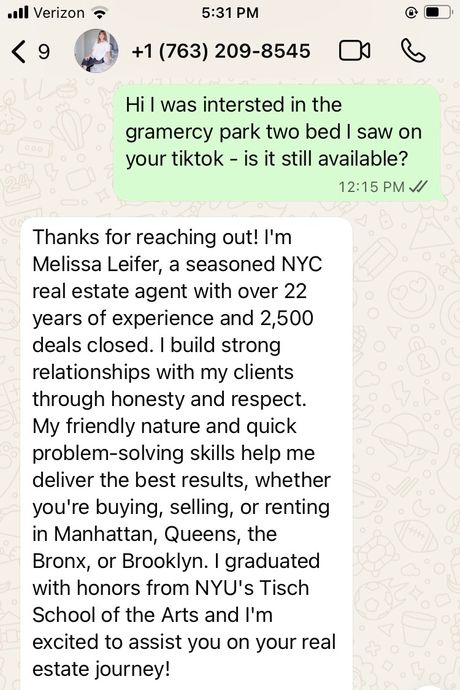

But I wanted to know what a prospective renter might experience after reaching out to these fake accounts. I sent a WhatsApp to keller_williams_realty, an account that had dozens of too-good-to-be-true prices (the actual Keller Williams website has a pop-up warning about scams impersonating Keller Williams agents), to inquire about a palatial and pristinely renovated Gramercy two-bedroom with inlaid hardwood floors, two wood-burning fireplaces, a washer-dryer, and a solarium off the main bedroom, all for $2,890 a month. (A surreal price for an apartment that looked like something out of a movie, which was vaguely explained by it being rent-stabilized.) Was it still available, I asked? “Thank you for reaching out! I’m Melissa Leifer, a seasoned NYC real estate agent with over 22 years of experience and 2,500 deals closed,” they responded, embellishing only a little on the number of transactions the real Melissa Leifer claims on her page. They told me they had graduated from NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts (also true of the real Leifer). Miraculously, the apartment they were advertising was still available despite being less than $3,000 a month in a highly desirable downtown neighborhood and on the market for several days at that point. After I sent over my credit score, income, and move-in date, “Melissa” sent back the move-in cost estimate — a very reasonable $4,890, with a $1,500 security deposit and a $150 application fee. Only the refundable application fee was due now. I pressed: When could I see it? First, I needed to submit the application, they replied. But I could see it tomorrow. Plus, I’d be eligible to see two other apartments if this didn’t work out.

The Gramercy two-bedroom I inquired about. When I checked back a few days later, the price had gone down, from $2,890 to $2,500.

I decided to press further. I asked why the listing wasn’t on the Keller Williams site. “We utilize our website for properties meant for sale and promote our rental apartments on TikTok because of its high engagement level,” they replied. This actually seemed sort of believable. I pushed a little further: Why wasn’t it on StreetEasy? Apparently, this follow-up — or more likely the fact that I hadn’t submitted my application or the fee — meant that I wasn’t a very promising prospect, and they stopped responding.

When I reached out to the real Melissa Leifer, she told me that the scammers have been impersonating her since February. She’d been commenting on the TikTok pages that the posts were fake, but then the account would block her. At one point, she reached out directly and told them, “I’m going to find you and I’m bringing your number to the cops.” “I was so angry,” she says. It didn’t work, she adds. The scammers just changed their numbers.

My conversation with a scammer. When I called the real Melissa Leifer, she told me they’d been impersonating her since February.

My conversation with a scammer. When I called the real Melissa Leifer, she told me they’d been impersonating her since February.

I caught up again with Sicari in early September, and she told me that the calls and emails had lightened up a little lately. She thought her warning videos on Instagram and TikTok might be helping, or it was the demise of the “cozy” and “unique” listing TikTok accounts that were recently removed. But it seemed just as likely that the scammers were moving on to other brokers, expanding their roster. I told Sicari about the fake Keller Williams agent I’d been chatting with, and she sent me a screenshot from Compass broker Jackie Soussan’s Instagram account: “Hello everyone, someone has been impersonating me on IG and TikTok using realtorjackiesoussan as their account name,” it read. “This Isn’t Me, It is a SCAM!” And even if the scammers’ Sicari impersonations are waning, people are still sending money to the fake her and getting mad at her about it. She told me she’d just been contacted by the Department of State. After months of trying to get the government to intervene, someone was finally taking action — just not in the way Sicari had hoped. Someone had reported the real Melissa Sicari. “They left several messages and sent me an email with a copy of the complaint,” she told me. “When I saw the $145 application fee, I knew it was the scammer.”

Sign Up for the Curbed Newsletter

A daily mix of stories about cities, city life, and our always evolving neighborhoods and skylines.

Vox Media, LLC Terms and Privacy Notice